The Homebush Saleyards

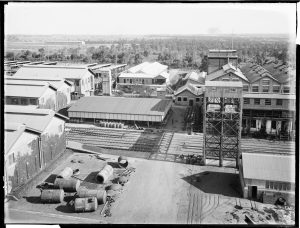

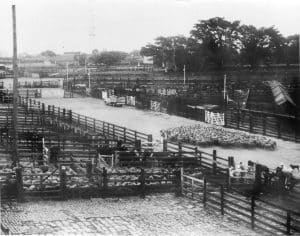

The Homebush Saleyards c.1920s-1930s. by Arthur Ernest Foster. Courtesy State Library of NSW

Long-term local residents may remember the smell of the Homebush Saleyards that once occupied the site of Sydney Markets, alongside Flemington Railway Station.

‘Flemington proclaims itself as you pass in the train. The smell of the cowyard is strong and unmistakeable. The wind carries it into your compartment and you look out and see the acres of stockyards, the city’s meat assembling centre.’[1]

For at least 130 years livestock were bought, sold, driven and herded in the Homebush and Homebush Bay districts.

Where there’s a growing city there is obviously a need for a regular food supply for the increasing population. Public abattoirs were established at Glebe Island during the 1850s. By that time there were a number of private stock saleyards in operation on the outskirts of Sydney, with the main one being Fullagar’s Cattle yards at modern-day Wentworthville, which had opened in 1845.

There was also a saleyard in Homebush.

In 1858, auctioneer, Henry Daniel Bury advertised that:

‘the advertiser has obtained a thousand acres of well watered and well grassed land securely fenced in at Homebush where all horses, cattle and sheep sent to him for sale can be depastured free of charge. Sales will be contracted by auction or by private contract, to suit the convenience of vendors or purchasers, at the sale yards at Homebush.’[2]

By 1868 there was a need for centralised saleyards. As there were only two sale days per week – and 14 different saleyards around Sydney – agents could not attend all sales. This meant that there was not enough competition and prices remained low. Producers missed out on a fair return for the 5,000 sheep and 1,000 cattle that were sold weekly around Sydney.[3]

In May 1870 the Corporation of Sydney (Sydney Council) received permission from parliament to establish public cattle saleyards within ten miles of Sydney. Several aldermen visited Melbourne to inspect the Newmarket saleyards at Flemington which were considered to set a high benchmark for desirability.

There was land available for sale at Petersham and the offer of land at Homebush, which was part of Wentworth’s estate.

Mudgee sheepbreeder and politician, George Henry Cox summed up the situation:

‘Homebush was within a reasonable distance of Sydney, and the trains ran to and fro several times in the day. At Homebush there were large grazing paddocks; and it was so far removed from the city that it would take many years before any large population settled there, whereas Sydney was increasing so fast that in all probability before many years Petersham would be within the city.’[4]

So, in 1870 cattle and sheep yards were built near Homebush Railway Station. The station had opened in 1855 which was a major attraction for local industry. Suddenly the Homebush district was easily accessible from both the city and country areas.

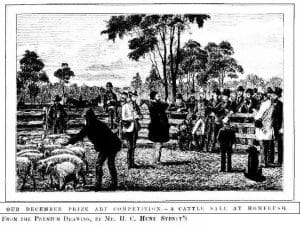

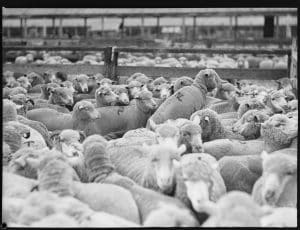

Although labelled a ‘cattle’ sale, the stock are obviously sheep. Apparently the term ‘cattle’ once referred to stock in general with ‘horned cattle’ denoting cows rather than sheep.

The Illustrated Sydney News and New South Wales Agriculturalist and Grazier 30 September 1881 p.12

These yards served the needs of Sydney for about 12 years but were considered quite primitive and there was concern about the welfare of the stock arriving there after long train journeys. Stressed, unhealthy livestock meant poor quality meat for consumers.[5]

Butcher and Alderman, Thomas Playfair (later Mayor of Sydney) agitated for better facilities and the decision was made to build new saleyards a short distance away at Flemington. Sydney Council resumed 29 acres of land from the Underwood Estate and purchased 11 and a half acres adjoining it. Construction commenced in June 1881.[6]

The new stockyards were opened on 1 November 1882 at a total cost of 60,000 pounds which included the land. Designed by the City Surveyor, the cattle yards covered an area of seven acres and the sheep yards an area of about four and a half acres. They could accommodate 1,200 cattle and 12,000 sheep. When fully completed, the new Homebush yards would accommodate 1,500 cattle and 20,000 sheep.[7] The suitability of the new site was assured by the opening of Flemington Railway Station in 1884 and Sturt’s Wentworth Hotel at about the same time.

During the opening of the saleyards, agent, Mr Badgery noted that he ‘regarded Homebush as a more appropriate name than Flemington for the yards. To call them Flemington would be copying Melbourne, and he disapproved of such copying.’ [8] The Newmarket saleyards at Flemington in Melbourne had already been in operation for about 20 years.

The Homebush Saleyards were used by a large number of stock and station agents, including Pitt, Son and Badgery and Hill, Clark & Co. A number of the agents lived locally in the spacious homes being built in Strathfield. In the early days all the sheep arriving at the saleyards were classed by only two men – Alfred Hall and Edward Prentice. Prentice Lane in Strathfield South was named for this family of local butchers and drovers. Only one man, Charles Hughes, classed the cattle. 100,000 sheep were sold during the new saleyards’ first year of operation in 1883.

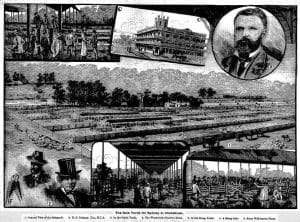

Australian Town and Country Journal 2 August 1884

By about 1890 there were more than 100 million sheep in Australia while the human population numbered about 3.1 million, although it quickly increased to approximately 4 million in 1901.

Several people recorded memories of the Homebush area during the 1890s. Artist and horse-lover, George Washington Lambert gravitated to the saleyards during his younger years:

‘It was the men and cattle and sheep that always drew me back to Flemington for in the back-country atmosphere they brought with them I was quite at home. One watched the sales, of course, but my main camping ground was the old pub at the top of the hill, isolated on the side toward Sydney, but commanding towards the west a great expanse of bushland and bare earth which the mobs of stock had ploughed into fine dust. Suburban though the place was, it wasn’t at all a bad imitation of the real bush.’[9]

Irene McEgan (nee Priora) remembered her childhood in the 1890s as: Animals bellowing, dogs barking, and the stockman’s whip cracking, and the dust.’[10]

Sale days went something like this:

‘Catch a train for Flemington at about 8.30 on any Monday or Thursday, and you will find yourself one of the crowd that are off to the fat stock sales at Homebush…. After the railway people have landed the sheep at Flemington the agents take charge of them and get them into the receiving yards… The yards themselves are a bewildering phantasmagoria of little square pens, with lanes between. Everything is clean as a new pin… Pens are of all sizes. Some have only thirty or forty sheep in them. Others have 300 or so.’[11]

Sale days could be incredibly long and often finished in darkness. Sheep were sold in the mornings and cattle in the afternoon. They were sorted, classed and ideally, rested, before they were sold by the agents, quickly branded and reorganised, most ready to be driven to the public abattoirs at Glebe Island on Monday and Thursday nights. Stock, especially cattle, could not be moved in great numbers during the day as it would have been much too dangerous and inconvenient for local residents. And so livestock were driven at night – herded in their thousands by drovers in darkness along 13km of road through a number of council areas – over many, many years. What could possibly go wrong?

Mrs E. Mansfield recalled those days:

‘Parramatta Road was much quieter in the early days but you had to be careful. On Monday and Thursday nights, cattle from Flemington saleyards were taken along the road on their way to Glebe Island for slaughtering and it was dangerous to be out. One night my Grandma was coming over and she left it a bit late. The cattle were already on the road, so she got herself into the creek and got lost. My father went looking for her and when he found her she was still in the creek calling out ‘I am lost…lost I are.’[12]

There were dangers for the drovers too. In 1896 drover, John Thurlow Seymour was killed when herding bullocks at the saleyards when one charged, pinning him against a fence.[13]

Homebush Saleyards c.1890-1910. Courtesy National Archives of Australia

No one was entirely happy with the saleyard situation – producers, buyers, residents and drovers alike. Although they provided employment for many local butchers, drovers and stock agents, local councils fought long and hard – and unsuccessfully – over many years for the removal of the saleyards from their doorstep. Not only was the driving of stock noisy, smelly, dangerous and inconvenient but local councils (and residents) feared the impact on property prices and lifestyle. In July 1899 a public meeting was held at Homebush seeking the establishment of abattoirs closer to the saleyards. And in 1903, Strathfield Council again protested about the damage to roads and footpaths caused by ‘the travelling multitudes of sheep and cattle.’[14]

Part of the problem too was that because the saleyards were owned by Sydney Council, local councils had no control over them other than trying to manage the movement of stock on local roads to and from the saleyards and mandate the hours that the droving could take place. This was an even bigger issue when councils disagreed about the times and routes that the stock could be driven.

Homebush Council was formed in mid-1906 and was very quickly concerned about the saleyards. In September 1906 the new council clerk twice visited the saleyards to ensure that stock were not moved before 6pm. In December 1907 Strathfield Council set down regulations for travelling stock in their municipality. In summer time no stock were to be driven between 7am and 6pm and in winter, no driving between 8am and 5pm.[15] The debates over droving times went on for years.

Finally, in 1907 the government resumed 367 hectares of the Homebush Estate for a new abattoir at Homebush Bay and construction began in 1910.

Meanwhile business remained healthy at the saleyards. By 1908 it was not unusual for 40,000 sheep to be sold in a day. And 1,500 cattle a day was regarded as a good muster. Monday was the big day for cattle and Thursday for sheep. In that year, Homebush Council claimed that more sheep and cattle passed through the Homebush municipality than any other suburban area and decided to compel drovers to keep cattle moving on Parramatta Road at a pace of not less than two miles per hour.[16]

In 1909 a writer to the Sydney Morning Herald complained that:

‘Mobs of sheep and cattle are encountered every few hundred yards for some miles on either side of Flemington, and it is a common sight to see several vehicles and motors work their way through them and emerge out of a dense cloud of dust. The drovers have no consideration for travellers, and no effort is made to enable them to pass. The dust is worse than a London fog, and a trifle more highly scented.’[17]

In June 1911 the Mayor of Strathfield, Alderman Capper addressed the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works about the nuisance of the stock yards.[18] He complained about the congestion of stock arriving at Flemington and advocated for saleyards to be built at the new abattoir. He also pleaded for control of them to pass to the government rather than to the city council. The Standing Committee agreed that saleyards should be built on the site of the new abattoir at Homebush Bay.

On 1 December 1911, after several days of severe heat, a tornado struck Homebush and Flemington just after 1pm and tore the roof off Pitt, Son & Badgery’s 150 yard-long cattle shed.[19]

Improvements were made to the saleyards after the establishment of the Meat Industry and Abattoirs Board in 1912. These included water to 100 extra sheep yards as well as in the lanes; the erection of a drovers’ shelter shed, buyers’ dressing room, and 83 dog kennels; and the purchase of a horse broom and water cart.[20] The Board also demanded an end to the tar branding of stock at Flemington as it was considered cruel and tanners complained about the state of the hide. The drovers protested as tar branding was their preferred option.[21] The unloading capacity at the railway station was also increased at this time.

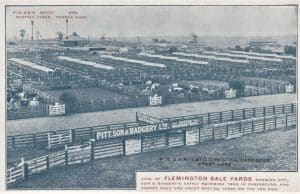

The stockyards of agents, Pitt, Son and Badgery featuring swimming baths to clean and refresh cattle before auction. The Wentworth Hotel can be seen in the top right-hand corner.

In January 1913 eight western suburbs councils expressed shared concern about the cost of maintaining the roads through their municipalities:

‘The cost of maintaining the stock route from Homebush to Glebe Island is a big item in the year’s expenditure of the Homebush, Strathfield, Concord, Burwood, Ashfield, Petersham, Leichhardt and Balmain councils, and for years past these councils have been agitating for the removal of the yards or a more suitable means of conveying the animals to the abattoirs. The fact that the abattoirs will be concentrated at Homebush Bay is being urged as a good reason why the saleyards should also be shifted, and in this way remove for all time any cause for complaint.’[22]

The following year (April 1914) brought new regulations from Homebush Council who specified that:

‘No flocks of sheep shall exceed 2000 in number, nor be driven at a rate of less than one mile per hour. No mob of cattle shall exceed 200 in number, nor be driven at a rate of less than two miles per hour. No mob of horses shall exceed 100 in number, nor be driven at a greater rate than four miles per hour. Each mob of cattle or horses shall be in charge of not less than two drovers, one of whom shall be in front to lead and the other behind.’[23]

Certain routes and driving hours were also mandated. The aldermen believed that these regulations would also assist land prices in the area.

A sheep sale at Homebush c.1915. Courtesy State Library of NSW

In January 1915 a meeting was held in Auburn to establish a local branch of the Association for the Relief of Travelling Stock. The assertion was made that during the previous two years 45,000 sheep and cattle had met agonising deaths on the railways.[24]

State Abattoir, Homebush Bay, 1927 by Arthur Ernest Foster. Courtesy State Library of NSW

The State Abattoir was finally opened at Homebush Bay in April 1915. Livestock now had a much shorter journey to slaughter as the land on which the abattoir was built was all but adjacent to the saleyards’ site. But there was still one major obstacle to the smooth driving of stock – Parramatta Road. When the decision was made to move the abattoirs to Homebush Bay, authorities insisted that a tunnel could be built under Parramatta Road to move stock. But the tunnel never eventuated. Instead, on Mondays and Thursdays a policeman from Strathfield would be on duty between 9am and 4pm to stop the traffic while the drovers moved their livestock. On other days the drovers had to fend for themselves.[25]

Cattle classer, Justin Slattery claimed that ‘Some motorists take pot luck whether they knock a bull over or the bull knocks them over.’[26]

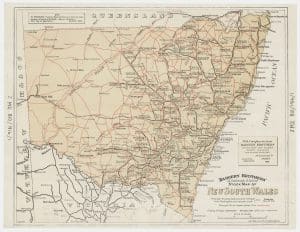

1916 stock droving routes of NSW. Courtesy State Library of NSW

Locals were still unhappy. During the 1920s there was even a Flemington and Homebush Saleyards Removal League to agitate for the saleyards’ relocation to Homebush Bay.[27] In 1926, the western councils tried to standardise the hours for driving stock between Homebush and Parramatta to between 10pm and 6am.[28]

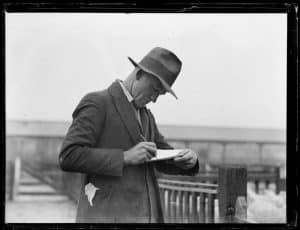

A day at the Saleyards c.1925. Courtesy Fairfax and the National Library of Australia

Accidents and incidents remained commonplace at the saleyards but none was more worthy of media attention than a day in September 1929. Picture the scene if you can.

‘The Sunday decorum of stations on the main suburban line was rudely shattered yesterday afternoon by a belligerent bull, which played havoc until it met an early doom.’[29]

After attempting to charge a steam train at Homebush Station, the runaway bull continued along the railway line. He charged along two separate platforms at Strathfield, scattering passengers, and then headed towards Burwood, narrowly missing several electric trains. He galloped straight through Burwood to Croydon, chased by six porters and five civilians in a motor lorry before finally being shot by one of the passengers near Summer Hill. The newspapers had a field day.

Homebush Saleyards c.1920s-1930s by Ernest Foster. Courtesy State Library of NSW

By 1933 Homebush Saleyards were handling more livestock than any other saleyard in the southern hemisphere and returned 22,000 pounds a year in profit. During the 50 years between 1882, when the saleyards opened, and June 1933, more than 130 million sheep and nearly 9 million cattle had been sold there. That was more than the total number of sheep then in the entire Commonwealth. The year ending 30 June 1933 was the record year when 4,088, 219 sheep and lambs were penned.[30] An article in October 1934 noted that the people of NSW consumed 200 pounds (90 kg) of meat per capita each year. This compared with 131 pounds in the USA, 144 pounds in Great Britain and 156 pounds in Canada.[31]

Homebush Saleyards 13 December 1937. Courtesy State Library of NSW

But the agitation to move the saleyards continued. In early 1938 the Farmer and Settler reported that:

‘The critics of Homebush stock selling centre have been, and are, legion. Ever since its inception as a Government-controlled concern, the centre has been subject to a constant barrage of comment, yet it goes on functioning like a well-oiled machine, and retains its position as premier stock selling centre of Australia… Homebush is a gigantic undertaking, and like all human works, has its faults.’[32]

Sheep in Shortland Avenue Strathfield c.1930s. Not all livestock went to the State Abattoir. Stock also travelled on Council approved routes through local municipalities. Courtesy Strathfield-Homebush District Historical Society

After WWII the state decentralised the slaughterhouses and new abattoirs were established in country areas.

In September 1949 a large black boar escaped from the saleyards and ‘took possession of a milk bar for nearly half an hour’ on a Sunday afternoon.[33]

An amendment to the Meat Industry Act in 1950 saw control of the State Abattoir moved to the Department of Agriculture with management vested in the Metropolitan Meat Industry Board of three members. The minister, E.H. Graham inspected the Homebush yards and decided that they needed upgrading. He also noted that the construction of saleyards had begun in 1916 on the abattoir side of Parramatta Road and he believed that this was still the best site 36 years later. He was also extremely concerned about the continuing dangerous crossing of the main Western Highway when stock headed to the abattoir.[34]

This was still the situation during the 1950s by which time the traffic on Parramatta Road had increased so dramatically that the drovers went on strike. Traffic lights were installed. These worked much like pedestrian lights and the traffic would have to stop while the stock were driven across when the drover would push the button again for the light to turn green.[35]

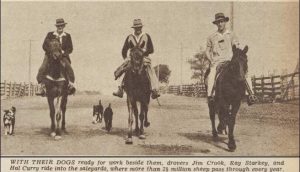

In 1950 the Australian Women’s Weekly featured the 340 sheep and cattle dogs and the 50 or 60 drovers still working at the saleyards. More than two and a half million sheep passed through the saleyards each year at that time.[36]

Australian Women’s Weekly 15 July 1950

An article by Truth in November 1953 highlighted the continued loss of stock and working dogs by cars.

‘…motorists killed, on an average, six sheep and one cow a week. About 60,000 sheep and 10,000 cattle go through Flemington stockyards weekly, and almost 90 per cent cross the Parramatta highway to the abattoir.’[37]

In 1955 NSW railways carried 18 million head of stock annually. And some of the same agents were still in business at Homebush Saleyards after many years. In 1955, an article in Farmer and Settler noted that Pitt Son and Badgery had been in business there for 73 years. Their sheep resting paddocks contained more than 40 separate yards, individually shaded by large trees and containing a modern trough. They also owned cattle resting paddocks with more than 20 separate yards, individually sheltered by a huge island shed, 650 feet long. Swimming baths for the cattle removed travel stains, cleaning and improving the appearance of stock before sale.[38]

Saleyards from Flemington Railway Station, 1959. Courtesy Strathfield Council

But ever since the abattoirs opened at Homebush Bay in 1915, the aim had been to move the saleyards to the same site and finally, in 1967 the Flemington yards closed after 85 years of service.

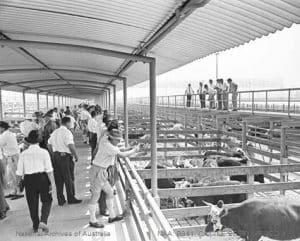

On 1 March 1968 new saleyards were opened at the State Abattoir by the Governor, Sir Roden Cutler. The 33 acre site could accommodate between 3,000 and 4,000 cattle, 35,000 sheep and between 3,500 and 4,000 pigs. An elaborate marble drinking fountain unveiled in 1896 to the memory of Thomas Playfair was relocated from Flemington to Homebush Bay in 1968 and now stands in Dawn Fraser Avenue, Sydney Olympic Park. The Homebush Bay saleyards lasted only 20 years with the abattoir closing in 1988 and the development of Sydney Olympic Park.

Auction of cattle at Homebush Bay, c.1968. Courtesy National Archives of Australia

In 1975 Sydney Markets opened on the site of the former saleyards and continues to operate there today.

After all these years, animal movement remains a matter of great importance as we have seen recently with the threat of foot and mouth disease in Australia. The stock routes though our local area were a significant factor in its development. Homebush, Homebush West and Homebush Bay played a major role in the meat industry of the entire state for many, many years.

By J.J. MacRitchie

Local Studies Advisor

References

[1] Sydney Morning Herald 27 April 1932 p.10 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16859073[2] Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer 20 November 1858 p.1 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/59869616

[3] The Goulburn Herald and Chronicle 22 July 1868 p.4 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/101477527

[4] Sydney Morning Herald 7 September 1870 p.17 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13223108

[5] Sydney Morning Herald 4 November 1882 p.11 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13526917

[6] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser 28 October 1882 p.762 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/161922900

[7] Australian Town and Country Journal 4 November 1882 p.15 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article70992675

[8] Evening News 2 November 1882 p.2 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/107997765

[9] The Home: an Australian Quarterly V.14 No.5 1 May 1933. ‘Choosing a career: an anecdote of George Lambert told by Arthur Jose.’ Vol. 14 No. 5 (1 May 1933) p.13 https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-371998265

[10] Mrs Irene McEgan 1890 https://strathfieldheritage.com/people/memories-oral-history/mrs-irene-mcegan-1890/

[11] Evening News 18 July 1908 p.3 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/114750873

[12] Early Years in Homebush – Mrs E. Mansfield https://strathfieldheritage.com/people/memories-oral-history/early-days-in-homebush/

[13] Evening News 7 March 1896 p.5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/109920233

[14] Sydney Morning Herald 10 March 1903 p.8 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article14494963

[15] Sydney Morning Herald 23 December 1907 p.11 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/14893885

[16] Sydney Morning Herald 1 May 1908 p.9 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article14930143

[17] Sydney Morning Herald 13 October 1909 p.14 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/28143326

[18] Australian Town and Country Journal 5 July 1911 p.4 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/263726547

[19] Daily Telegraph 2 December 1911 p.13 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/239204252

[20] The Sydney Stock and Station Journal 2 September 1913 p.2 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/124124722

[21] The Sun 13 September 1912 p.11 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/228824227

[22] The Sun 6 January 1913 p.5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/228695950

[23] The Sun 22 April 1914 p.7 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/229238191

[24] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers’ Advocate 23 January 1915 p.6 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/86108302

[25] Scott, Vincent (Tibby) A History of Meat in Sydney. Sydney, NSW: The Metropolitan Meat Industry Board, 2001

[26] The Sun 30 November 1937 p.3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article232009052

[27] The Sun 29 October 1926 p.10 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article224122269

[28] Evening News 30 April 1926 p.7 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/117279213

[29] Daily Telegraph 30 September 1929 p.3 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/246290808

[30] The Farmer and Settler 18 January 1934 p.5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/117744995

[31] The Farmer and Settler 18 October 1934 p.11 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/117741695

[32] The Farmer and Settler 13 January 1938 p.5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/117170380

[33] Daily Examiner (Grafton) 5 September 1949 p.2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article195104387

[34] The Farmer and Settler 25 January 1952 p.14 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/117535844

[35] Scott, Vincent (Tibby) A History of Meat in Sydney. Sydney, NSW: The Metropolitan Meat Industry Board, 2001

[36] Australian Women’s Weekly 15 July 1950 p.13 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article46074213

[37] Truth 8 November 1953 p.12 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article168103923

[38] The Farmer and Settler 25 November 1955 p.3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article123146466