The Curious Case of Constance Kent

Constance Emilie Kent, 1862

The death occurred of Miss Ruth Emilie Kaye at the Loreto Convalescent Home in Albert Road, Strathfield on 10 April 1944. She had celebrated her 100th birthday just two months earlier when Strathfield Council sent her a sheath of gladioli, eight feet long. Another friend sent a bottle of champagne and she also received a telegram of congratulations from the Governor-General.[1] A small party celebrated her milestone.

The Sunday Sun and Guardian 6 February 1944 p.2

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article231830978

After her death, obituaries praised her nursing work and selfless care of patients over many years in institutions such as the Lazaret Home for Women Lepers at Little Bay and the girls in her care at the Parramatta Girls’ Industrial School. She had also spent many years as Matron of the Maitland Nurses’ Home.

According to an article in the Sun: ‘Only since her 99th anniversary has Miss Kaye given up walking to church regularly on Sundays and taking part in outside social activities.’[2]

It seems likely that she had attended St. Anne’s Anglican Church on Homebush Road. The newspapers also reported that Emilie Kaye had been born in Devonshire, England and came from a large family. She had travelled, settled in Australia during the 1860s and trained as a nurse in her forties.[3]

It was many years after her death that the shocking true story of Ruth Emilie Kaye’s past was revealed.

Indeed, she had been born in Devon and had a number of siblings, but her name was really Constance Emilie Kent. After the early death of her mother, her father, the Inspector of Factories for the southern and western counties, had married their governess. This led to some jealousy among the older children of the favouritism shown to their younger half-siblings. The family settled at Road Hill House near Frome on the Wiltshire/Somerset border and Constance, resentful of her stepmother, tried to run away. She was sent to boarding school.

Road Hill House

But one night in late June 1860, when the second Mrs Kent was heavily pregnant with her fourth child, the family was rocked by tragedy when Constance’s almost four-year old half-brother, Francis (known as Saville) was abducted from the house and killed in an outdoor lavatory. His throat had been cut.

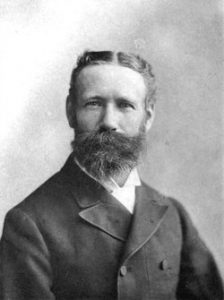

Jonathan Whicher

Enter the local police and soon, Scotland Yard who sent Jonathan (Jack) Whicher from London to solve the crime. The children’s nursemaid was an early suspect, as was Mr Kent himself, but so too was Constance, aged 16 and her younger brother, William, both home from boarding school. Jack Whicher strongly suspected Constance, based largely on her missing nightdress. However in Victorian era society it was almost unthinkable that a lowly detective could suspect and implicate a gentle-born girl of the middle classes. And yet he did – with good reason. Amid rumours of adultery and madness, the family’s secrets were both laid bare and embellished for public consumption. It is generally thought that author Wilkie Collins later based elements of The Moonstone and Sergeant Cuff on Whicher and the Road Hill murder.[4] But Whicher himself was ridiculed at the time.

Constance was arrested and questioned about the child’s death but was released due to insufficient evidence. Amid so much public scrutiny, she could not return to the fractured family and was sent by her father to school in France. Later she became a probationer and nurse trainee with the Anglican nuns at St. Mary’s Convent in Brighton.

Shockingly, in 1865, a penitent Constance confessed to the crime – initially to Reverend Arthur Wagner in Brighton. He accompanied her to authorities in London with a written statement.[5] Convicted, she was sentenced to death by hanging, commuted by Queen Victoria to a life sentence of penal servitude. Her stepmother died just a month later. Public interest in the case revived to such an extent that Constance was considered the most famous – or infamous – woman in England. Her likeness was even taken in wax by Madame Tussaud’s.[6]

Constance Kent

Constance served 20 years of her sentence in four different prisons and was released in 1885, aged 41. She had petitioned the authorities on many occasions for her release. Her brother, William Saville Kent, a marine biologist [7] with whom Constance had been close, had emigrated to Australia, seeking anonymity and escape from the family scandals. Constance decided to follow him, reinventing herself as Ruth Emilie Kaye and disappearing into obscurity. Occasionally the British press wondered what had happened to the infamous murderess, concluding that she had probably emigrated and died overseas.

William and his second wife had migrated to Tasmania in 1884. His half-sister, Mary Amelia, aged 29 accompanied them. They were joined in Hobart by the younger three half siblings in 1886.[8] William took jobs throughout Australia before finally returning to Britain, where he died in 1908, but the rest of the family remained in Australia. Acland, born just a few weeks after the murder, died in Bendigo in 1887. Mary Amelia and Florence settled in NSW, although they had little or no contact with Constance. Eveline died in Melbourne in 1940.

William Saville Kent c.1892

During the typhoid epidemic of 1890, an appeal for volunteers to nurse them was made and Constance, then in Melbourne, volunteered, nursing patients in tents scattered throughout the grounds of Prince Alfred Hospital. She went on to train as a nurse. Later she settled in Sydney where she worked as sister-in-charge of the lepers at the Coast Hospital at Little Bay [9] before spending 11 years as matron of the Parramatta Girls’ Industrial School.[10] She was appointed in 1898 after a riot and subsequent inquiry into conditions there led to the replacement of the matron, although she also lowered her age by five years to get the job.[11] At the time an article about the Road murder was published in the Truth newspaper in April 1899, no one could have known that the murderess was then holding the very respectable position of matron in Parramatta.[12]

The Lazaret at the Coast Hospital, Little Bay, c.1900. Courtesy Randwick Library

Parramatta Girls’ Industrial School, c.1910. Courtesy Parramatta Female Factory Precinct

https://www.parragirls.org.au/parramatta-girls-home

Muster, Parramatta Girls’ Industrial School, c.1910. Courtesy Parramatta Female Factory Precinct. https://www.parragirls.org.au/parramatta-girls-home

In 1910 ‘Sister Ruth’ briefly opened an electric treatment clinic in Mittagong [13] but by 1911 she had settled in Maitland where she ran an aged care home for retired nurses.[14] She was Matron of the Pierce Memorial Nurses’ Home in Maitland from 1911 to 1932, retiring from there aged 88. It is also thought that she worked in military hospitals during the Great War.

In 1927, aged 84, she was taken on a plane flight by Captain Hammond, a Strathfield World War I pilot, which she enjoyed immensely.[15]

In 1928 a curious letter was received by the British publishers of a book titled The Case of Constance Kent by John Rhode. It was addressed to the publisher, Geoffrey Bles and had been sent from Sydney. Becoming known as The Sydney Document, the 3000-word letter objected to the aspersions of insanity cast upon the first Mrs Kent and outlined the acrimonious relationship between Constance and the second Mrs Kent. Although written in the third person, the letter could only have been written by Constance herself.

Miss Kaye’s final years were spent at the Loreto Convalescent Home, Strathfield where her 100th birthday was celebrated in style. It was not until the 1970s that the truth of her identity was widely discovered. Shortly before her death she had asked her niece to visit her in Strathfield. Olive was the daughter of Mary Amelia Kent, Constance’s half-sister. However Olive did not know that Miss Kaye was her aunt. She had known her only slightly in Maitland:

‘Miss Kaye was living at the Nurses’ Home in West Maitland when I first saw her, which was 4 years after my mother’s death being 92 years old then she had retired. She said she had known my mother and wanted to meet her daughter. My husband drove me up to Maitland and we both liked the little old lady.’[16]

In later years Olive wrote:

‘Later Miss Kaye went to Sydney to live in Strathfield. I was invited to go down to this 100th birthday party and did so. She was a really wonderful old lady, did not wear glasses to read and [was] quite jolly, everybody seemed very fond of her too.’[17]

Shortly before her death Miss Kaye revealed the truth about her identity during Olive’s visit to Strathfield. Mary Amelia, who was aged five when her brother was killed, had told her daughter only that there had been a family tragedy and Olive had not asked for details. During the 1970s and 1980s Olive was contacted by a number of researchers interested in the story of her aunt.

Over the years there have been many books written and theories explored to explain the Road Hill murder. A number of them have suggested that Constance was innocent of the crime and had confessed to protect another member of the family, possibly her brother, William.

The truth of the matter died with Constance Emilie Kent at the Loreto Convalescent Home in Strathfield in 1944.

By J.J. MacRitchie

Local Studies Advisor

References

[1] The Sunday Sun and Guardian 6 February 1944 p.2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article231830978[2] ibid

[3] Sydney Morning Herald 11 April 1944 p.4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17866496

[4] Sunday Mail (Brisbane) 27 January 1929 p.26 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article97689482

[5] Leader (Melbourne) 22 July 1965 p.8 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/197035855

[6] Walker, Wendy Imagination and Prison. http://wendywalker.com/pdfs/wendy-walker-imagination-prison.pdf

[7] A. J. Harrison, ‘Saville-Kent, William (1845–1908)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/saville-kent-william-13185/text23869, published first in hardcopy 2005, accessed online 21 February 2022.

[8] Summerscale, Kate (2008) The Suspicions of Mr Whicher or the Murder at Road Hill House Bloomsbury, London p. 283.

[9] Illustrated Sydney News 3 April 1890 p.26 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/63610702

[10] The Richmond River Express and Casino Kyogle Advertiser 4 December 1908 p.5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/123973155

[11] Parry, Naomi ‘The Parramatta Girls Home’ Dictionary of Sydney, 2015 https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/the_parramatta_girls_home

[12] Truth 2 April 1899 p.3 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/168087908

[13] Robertson Advocate 11 January 1910 p.2 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/117150325

[14] Walker, Wendy Imagination and Prison. http://wendywalker.com/pdfs/wendy-walker-imagination-prison.pdf

[15] Singleton Argus 24 December 1927 p.3 http://nla.gov.au/nla/news-article81112026

[16] Kyle, Noeline (2009) A Greater Guilt: Constance Emilie Kent and the Road Murder. Brisbane: Boolarong Press p.213, 216 https://books.google.com.au/books?id=OTurMQaOQqwC&pg=PA214&lpg=PA214&dq=shirley+richards+olive+bailey&source=bl&ots=rrEykqUbSZ&sig=ACfU3U2tB6HJI4YC_Ot26vw7rPXVSjAd_Q&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjhsqWv69bwAhVIdCsKHayfB8YQ6AEwDXoECAIQAw#v=onepage&q=shirley%20richards%20olive%20bailey&f=false

[17] ibid p.216

Other Sources

Kyle, Noeline J. ‘Kaye, Ruth Emilie’ Dictionary of Sydney, 2012 https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/kaye_ruth_emilie

The Passing Tramp: Wandering through the mystery genre, book by book.

http://thepassingtramp.blogspot.com/2012/06/major-street-and-miss-kent-case-of.html

The Maitland Mercury. https://www.maitlandmercury.com.au/story/2545451/double-life-of-ruth-kaye/

Telegraph (Brisbane) 1 December 1928 p.15 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article178466388

Pipiwiki https://pipiwiki.com/wiki/Constance_Kent

Sunday Times 4 November 1900 p.11 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/126285564

The Suspicions of Kate Summerscale podcast

https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/archived/bookshow/the-suspicions-of-kate-summerscale/3077078